Artifacts

1989

Russian Crime Statistics, 1980–1996

Nothing characterized the everyday experience of the urban Russian 1990s like crime; as shown in this first comprehensive statistical study of the 1990s, crime was just as bad as everyone had known. But the numbers also reveal some unexpected trends.

Klei-Moment

Made by the German Henkel company, Moment glue was a staple of post-Soviet hobbyists. It also became one of the prefered drugs among the post-Soviet youth. The brand name became synonymous with huffing itself.

Test 1989

An item from 1989 to test date searching.

Early Vzgliad parodies itself

A 1988 celebration of a year of Vzgliad, where several sketch comedy artists parody and recapitulate Vzgliad's casual, sincere, freewheeling style of television programming

Putting the "Spotlight" on an experimental three-hour line for Soviet luxury clothes

Prozhektor Perestroiki [Perestroika's Spotlight], a glasnost-era televised investigative journalism project, investigates a three-hour line for luxury clothes at the recently opened Luxe Fashion Center, where the reporters discover the problem of supply and demand in the USSR.

Soviet technical intelligentsia learns Reaganomics on the Chto? Gde? Kogda? gameshow

Chto? Gde? Kogda? [What? Where? When?], a long-running high-brow quiz show for the late Soviet technical intelligentsia, debates the economic principles of Soviet private enterprise in the heat of Perestroika’s economic reforms in 1988

"Can't Live Like This": Imperial nostalgia as a post-Soviet Russian project

Tak zhit' nel'zia [Can't Live Like This], excerpt from Stanislav Govorukhin's influential documentary on the late Perestroika malaise and the way out of it

Primetime hypnotic tele-healing seances with Kashpirovskii

Anatolii Kashpirovskii, the psychic and guru of Perestroika era's "new thinking" uses the power of suggestion to heal the Soviet people from all ailments physical and spiritual

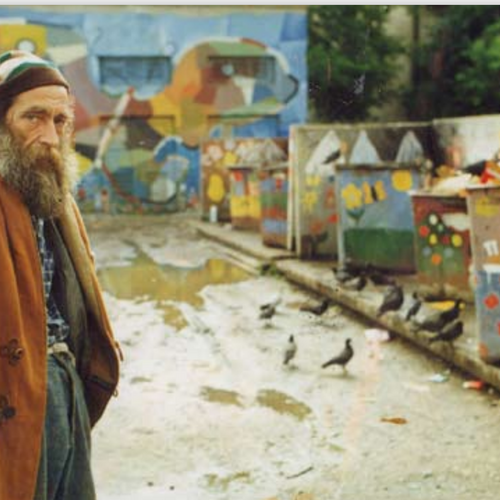

The Collective Society “Kartinnik”[”Picture-man”] with B.U.Kashkin in front of painted Ural Electro-Technical Institute rubbish pins. 1993.

The bearded B.U.Kashkin stands in front of a set of trashbins which have been painted with bright, colorful scenes of trees, butterflies and flowers. Pigeons are digging through the garbage and mud apparent throughout the site.

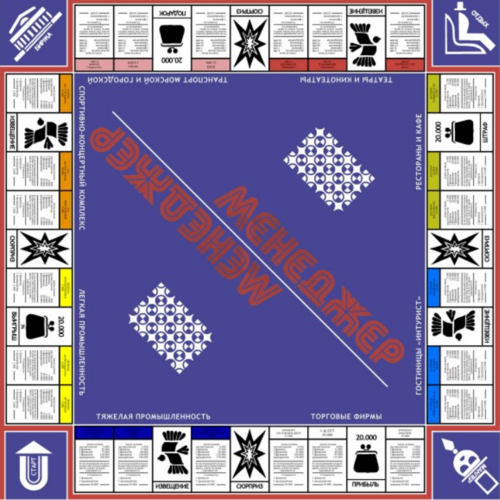

Manager Board Game 1st edition

A square, indigo board game similar to Monopoly, but reading "Manager". Manager, which became the most successful Monopoly-like made in the former Soviet Union, initially presented itself as scientific and rational in its promise of capitalist success.

“Dictatorship of Conscience”

Play by Mikhail Shatrov that opened at the Lenin Komsomol Theather in Moscow, Feb. 1986

Chumak sends morning healing vibes to Perestroika audiences

A healing seance with TV-psychic Allan Chumak in 1989, during the morning newscast, “120 Minutes.” Works on people, their drinking water and their creams.

Perestroika Women Speak to US Women

A clip from one of many Perestroika-era televised conversations between American and Soviet "regular people," in which they find common ground with the help of long-time Soviet propagandist and future star of liberal post-Soviet TV, Vladimir Pozner

Urlait Music Journal (Samizdat) 1985-1992

Moscow's samizdat music journal, which followed in the footsteps of Lenigrad's Roksi while forging a new journalistic style. The journal positioned itself to in many ways reject the Leningrad scene. Despite Moscow-based bands generally leaning towards a more avant-garde, art-rock aesthetic, Urlait made a point to promote so-called "national rock." According to Urlait's founder I. Smirnov, bands like DDT, DK, and Oblachnyi Krai (Yuri Loza) were said to be "oriented towards national problems, in opposition to estrada and the confluence of Western and domestic cultural traditions."

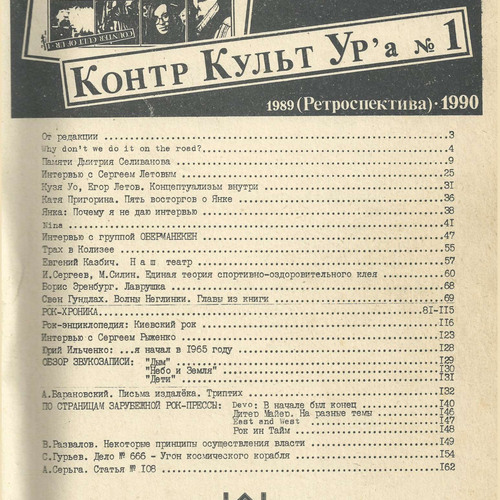

Kontr Kult Ur'a Music Journal (Samizdat) 1989-1991

Kontr Kult Ur'a was envisioned as an ideological reincarnation of Urlait, which was deemed by the new editorial board as "cult-like" and "radically positioned." The journal also was one of the first samizdat rock zines in Moscow and Leningrad to prominently feature and promote Siberian punk rock, including Egor Letov, Civil Defence, and Yanka.

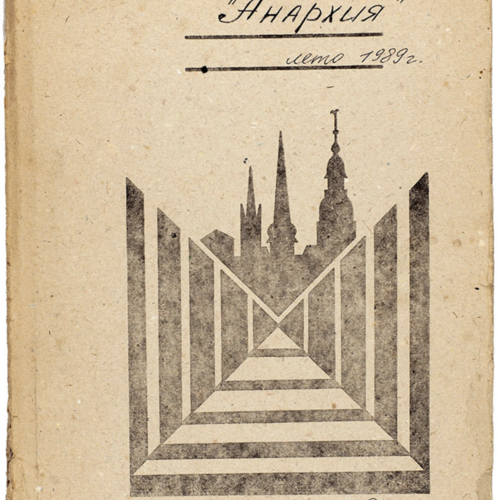

Anarkhia Music Journal (Samizdat)

According to rock historican Alexander Kushnir, Tiumen's samizdat music zine Anarkhia served as "the Bible of western Siberian punk rock," standing in opposition to the other Soviet rock samizdat publications with its strict affinity to punk as its central aesthetic ideology.

Tusovka Music Journal (Samizdat)

A central zine of the Siberian underground music community. One of Tusovka's central feats was duping the KGB into allowing the continuation of its publication and dissemination. Before the first issue went to print, the journal's founder Valerii Murzin took the bold step of delivering the pre-print manuscript of the journal to his local KGB office, in this way guaranteeing the publication's survival.

Band Survey from the Leningrad Rock Club completed by Sergei Kuryokhin of Pop Mekhanika

An official rock club survey in which Sergei Kuryokhin utlilizes the late-Soviet aesthetic of stiob and performative socialism to underscore the club's dependence on the KGB

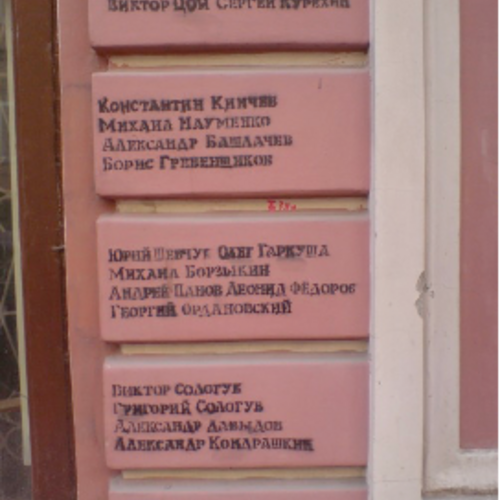

Leningrad Rock Club

A wall of graffiti in the courtyard of the Leningrad Rock Club (1981-1991) on 13 Rubinshteyna Street in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), which featured fan street art dedicated to USSR's most revered rock-music collectives. When the wall was painted over in 2010 by the bulding's new proprietor, this caused a public outcry from both rock fans and the many surviving musicians from that era, who sought to preserve the LRC's legacy and designmate the wall and the building a historical landmark.

Meaning of pluralism on Vzgliad

A conversation about pluralism between Evgeny Dodolev and Alexander Liubimov, after an expose on Nina Andreeva

Top Secret: Investigative Journalism and True Crime During Perestroika

Sovershenno sekretno, the first privately owned periodical in Soviet Russia since 1917, showcased a combination of transparency and sensationalism that became a distinguishing feature of journalistic writing in the post-Soviet period.

The World Made of Plastic Has Won

Egor Letov performs his song “Moia oborona” (My defense), during his “concert in the hero city Leningrad,” part of Grazhdanskaia oborona’s 1994 tour Russkii proryv (Russian breakthrough).

Mumiy Troll's Breakthrough “Utekai” (Take Off) Becomes the Song of the Year 1997

Video and lyrics of Mumiy Troll’s 1997 breakthrough song “Utekai” (Beat it) displaying the combination of surrealism, dark humor, and provincial romanticism that comes to shape the band’s trademark style.

Tanks in Lithuania

Pravda coverage of Soviet tanks in Vilnius, January 1991

The First (Home-Made) Post-Soviet Independent TV

The Saint Petersburg “New Artists” stage a meeting of the committee “anti-state of emergency” on their “Pirate Television,” declaring their support of Yeltsin against the group of communist hardliners who led the coup d’etat against Gorbachev on August 19, 1991.