Artifacts

1987

Russian Crime Statistics, 1980–1996

Nothing characterized the everyday experience of the urban Russian 1990s like crime; as shown in this first comprehensive statistical study of the 1990s, crime was just as bad as everyone had known. But the numbers also reveal some unexpected trends.

Klei-Moment

Made by the German Henkel company, Moment glue was a staple of post-Soviet hobbyists. It also became one of the prefered drugs among the post-Soviet youth. The brand name became synonymous with huffing itself.

Putting the "Spotlight" on an experimental three-hour line for Soviet luxury clothes

Prozhektor Perestroiki [Perestroika's Spotlight], a glasnost-era televised investigative journalism project, investigates a three-hour line for luxury clothes at the recently opened Luxe Fashion Center, where the reporters discover the problem of supply and demand in the USSR.

“Dictatorship of Conscience”

Play by Mikhail Shatrov that opened at the Lenin Komsomol Theather in Moscow, Feb. 1986

Sovetskii Ekran with K. Kinchev on the cover

Popular film magazines like Soviet Screen (Sovetskii Ekran), were instrumental in establishing rock musicians as cultural icons. Volume 7 (1987) publication places Konstantin Kinchev, frontman of the Leningrad band Alisa, on the cover of its “youth issue” (molodezhnyi vypusk) in an effort to promote the Valerii Ogorodnikov’s film The Burglar (Vzlomshchik, 1987) in which Kinchev plays the lead role.

Perestroika Women Speak to US Women

A clip from one of many Perestroika-era televised conversations between American and Soviet "regular people," in which they find common ground with the help of long-time Soviet propagandist and future star of liberal post-Soviet TV, Vladimir Pozner

Musical Ring (Музыкальный Ринг). Television program. Musical guest: Sergei Kuryokhin and Pop-Mekhanika. (February 1, 1987.)

Making its debut in 1984, Musical Ring was a Perestroika-era Soviet television program, dedicated to showcasing new musical talent and fostering a live audience Q&A. This 1987 segment features composer and avant-garde jazz pianist Sergei Kuryokhin and his band Pop Mekhanika. Throughout the episode Kuryokhin artfully wields the postmodern rhetorical weapon of styob, imbuing formal musical discourse with farce, an artistic and communicative device that became one a defining mode of expression during perestroika and the early post-Soviet period.

Urlait Music Journal (Samizdat) 1985-1992

Moscow's samizdat music journal, which followed in the footsteps of Lenigrad's Roksi while forging a new journalistic style. The journal positioned itself to in many ways reject the Leningrad scene. Despite Moscow-based bands generally leaning towards a more avant-garde, art-rock aesthetic, Urlait made a point to promote so-called "national rock." According to Urlait's founder I. Smirnov, bands like DDT, DK, and Oblachnyi Krai (Yuri Loza) were said to be "oriented towards national problems, in opposition to estrada and the confluence of Western and domestic cultural traditions."

Tusovka Music Journal (Samizdat)

A central zine of the Siberian underground music community. One of Tusovka's central feats was duping the KGB into allowing the continuation of its publication and dissemination. Before the first issue went to print, the journal's founder Valerii Murzin took the bold step of delivering the pre-print manuscript of the journal to his local KGB office, in this way guaranteeing the publication's survival.

Band Survey from the Leningrad Rock Club completed by Sergei Kuryokhin of Pop Mekhanika

An official rock club survey in which Sergei Kuryokhin utlilizes the late-Soviet aesthetic of stiob and performative socialism to underscore the club's dependence on the KGB

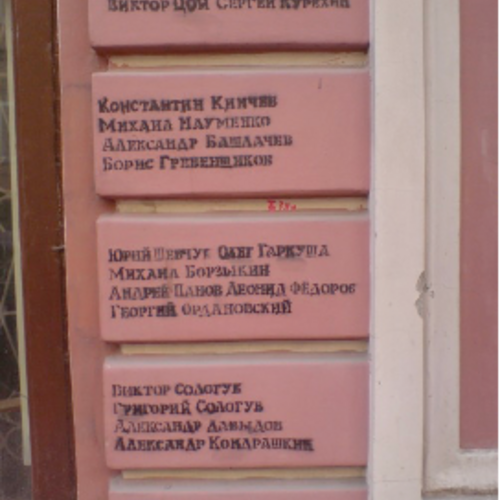

Leningrad Rock Club

A wall of graffiti in the courtyard of the Leningrad Rock Club (1981-1991) on 13 Rubinshteyna Street in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), which featured fan street art dedicated to USSR's most revered rock-music collectives. When the wall was painted over in 2010 by the bulding's new proprietor, this caused a public outcry from both rock fans and the many surviving musicians from that era, who sought to preserve the LRC's legacy and designmate the wall and the building a historical landmark.

The World Made of Plastic Has Won

Egor Letov performs his song “Moia oborona” (My defense), during his “concert in the hero city Leningrad,” part of Grazhdanskaia oborona’s 1994 tour Russkii proryv (Russian breakthrough).

Mumiy Troll's Breakthrough “Utekai” (Take Off) Becomes the Song of the Year 1997

Video and lyrics of Mumiy Troll’s 1997 breakthrough song “Utekai” (Beat it) displaying the combination of surrealism, dark humor, and provincial romanticism that comes to shape the band’s trademark style.