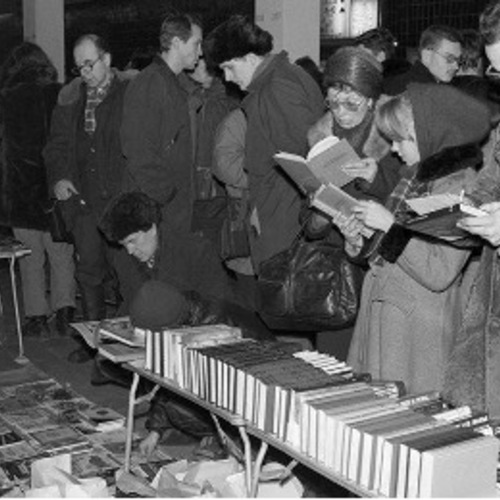

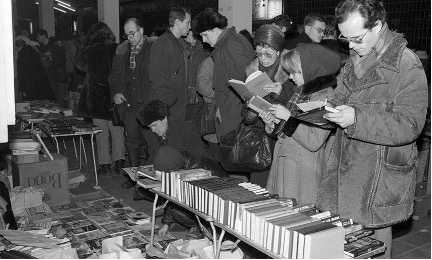

Olympic Stadium Book Market

Olympic Stadium Book Market, 1990s. Photographs by Robert Netelev, TASS.

Source

Description

The center of the post-Soviet book trade made its home in the corridors of the enormous stadium built for the 1980s summer games in Moscow. It was chaotic, even dangerous, and an embarrassment of riches.

Era

Post-Soviet

Date

1993-2019

Annotation

Olympic Stadium (Olimpiiskii sportivnyi kompleks), built for the 1980 Olympic Games, is located northeast of the center near the Prospekt Mira metro station. When built, it was the largest covered sports arena in Europe, holding that title until 2017. In December 1987, it hosted the first western rock band to play in the Soviet Union, Uriah Heep, and went on to host concerts from Pink Floyd and Black Sabbath before 1991. But the stadium complex played its most important role in the post-Soviet public sphere only later, and not for the events it hosted inside, but for the market that burgeoned in its outer corridors. In the wake of the January 1992 Presidential decree on free trade (ukaz o svobodnoi torgovle), many public spaces quickly turned into makeshift marketplaces, attracting merchants and buyers of everything from homegrown produce to cigarettes and imported clothing. One of the first markets in Moscow, Izmailovo, soon became too small for a booming business—the book trade—and in 1993, a group of publishers got together an rented the spacious outer corridors of Olympic stadium for the booming trade in the printed word.

The Olympic book market occupied four floors across the south and west faces of the stadium and worked both as a wholesale and retail distributor. In the early 1990s, as translations of western bestsellers—some authorized, many pirated (Steven King, for instance, first heard of his Russian translation from a bestseller list, not from a publisher or a translator)—flooded the market, print runs often running to 100,000 or more would arrive at the stadium early in the morning. As one denizen of the market recalls: “a truck would come in with some book, five thousand packs. Half would be sold immediately, as soon as the truck got into the loading dock. People were standing in line, they were tossed packs. They grabbed them and took them away somewhere.” These were mostly Moscow retailers—buyers not only for the large bookstores in town, but also for the various holdings of newsstands and kiosks that dotted the city, including, at that time, in the Metro. The balance of a print run was sold at the market itself, which was open to both wholesale and retail shoppers. But it wasn’t for the faint of heart, “Walking around Olympic Stadium was terrifying,” remembers one buyer, “packaging was always thrown into the aisles, everywhere was flooded with that packing paper.” And of course there was no climate control, so in the summer months, “it got so hot in there that people fainted.”

The market was not only the center of the Moscow book trade, it was also a “Mecca for book pilgrims from all of Russia.” As Soviet distribution networks broke down, provincial centers—even relatively large cities—found themselves cut off from the booming publishing industries of the capitals. Wholesalers traveled to Moscow, sometimes thousands of kilometers by car, to supply the local book trade, establishing informal exchange networks that sometimes faded, sometimes formalized as the economy stabilized throughout the 1990s. By the mid-1990s, the market had become a sometimes romanticized symbol of the confluence of free trade and the free press. “At Olympic commodity-exchange values had long held sway,” Lev Gurskii wrote in a 1995 murder-mystery set in the book industry. “It was a whirlpool that sucked into its maw millions of volumes in hardback and softcover, in cellophane and in dustjackets. And it was simultaneously a cornucopia through which any publication, printed wherever, could find its way to any place in the country. Olympic stadium was a stock exchange, a barometer, an academy of sciences and a gas pump, a great magnet for everyone who was ready to spend money on paper smeared with typographic ink and bound in quarto or in folio, and even more so for those who could turn paper into money.”

Associated People

Gurskii, Lev and Arbitman, Roman

Geography: Place Of Focus

Moscow

Bibliographic Reference

Oleg Matveev, “V zharu vse progrevalos’ tak, chto liudi padali v obmorok,” Moslenta, 1 Feb 2019. Web. https://moslenta.ru/city/v-zharu-vse-progrevalos-tak-chto-lyudi-padali-v-obmorok.htm

Explore Related Artifacts