Kletchataia sumka, Chelnoki, and Ostap Bender

Description

An entry in Argumenty i fakty's occasional column "Ugolok O. Bendera," gave advice to beginning "chelnoki," or small trade merchants who would travel—some across international borders—to find cheap items and sell them at markups back home. The checkered bag became a symbol of these petty merchants and of the hand-to-mouth trade of the 1990s

Date

1998

Annotation

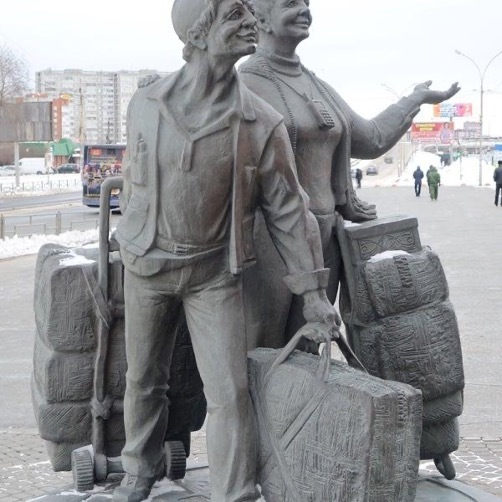

The checkered bag became a ubiquitous feature of train, bus, and ferry routes after the fall of the Soviet Union, especially those close to international borders. Light, cheap, and virtually indestructible, these polypropene bags became the luggage of choice for a whole new class of merchants who would have—only years before—been guilty of the Soviet crime of speculation. In droves, they would cross borders to Finland, China, Poland, or wherever something—anything—might be cheaper or easier to acquire than it was in Russia. With checkered bags stuffed to gills, they would return by the same bus, train, or ferry, and sell their goods in the local markets that bourgeoned in every city and town throughout the former Soviet Union. They became known as Bale Bags (sumka baul) or “Chelnok” Bags (sumka chelnoka), after the slang term for these new petty merchants. Chelnok, the term for a weaving shuttle, which is passed back and forth through the shed in loom weaving, took on the metaphorical meaning of someone who moves between two sides of the border, shuttling back and forth, and weaving the sides closer together. Though the chelnoks were more often mocked than praised at the time, they did much of the heavy lifting that opened markets in the post-Soviet years. In 2009 Yekaterinburg even erected a monument to the chelnoks, which prominently features the checkered bag.

The checkered bag was not just a post-Soviet phenomenon. It became popular throughout the former Eastern bloc. Former Yugoslav author Dubravka Ugresic, for instance, suggests including it in her personal museum of state socialism:

It was just a plastic carry-all. What made it special was that it had red, white, and blue stripes. It was the cheapest piece of hand luggage on earth, a proletarian swipe at Vuitton. It zipped open and shut, but the zip always broke after a few days. […] the plastic bag with the red, white, and blue stripes made its way across East-Central Europe all the way to Russia and perhaps even farther—to India, China, America, all over the world. It is the poor man’s luggage, the luggage of petty thieves and black marketeers, of weekend wheeler-dealers, of the flea-market-and-launderette crowd, of refugees and the homeless. Oh, the jeans, the T-shirts, the coffee that traveled in those bags from Trieste to Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria….The leather jackets and handbags and gloves leaving Istanbul and oddments leaving the Budapest Chinese market for Macedonia, Albania, Bosnia, Serbia, you name it. The plastic bags with the red, white, and blue stripes were nomads, they were refugees, they were homeless, but they were survivors, too: they rode trains with no ticket and crossed borders with no passport.

Bibliographic Reference

"Rokovye koftochki: Ugolok O. Bendera," Argumenty i fakty, 8 July 1998 (no. 28).

Explore Related Artifacts